Prospecting for Literature

Songcatcher Helen Hartness Flanders collected and preserved the musical heritage of New England, leaving behind a treasure trove of songs and stories.

(See below for audio and video samples of the songs she caught.)

The year is 1939. War brews across the ocean, but here in Springfield, Vermont, nestled in the Black River valley at the foot of the Green Mountains, it is early November, and nature’s brilliant display of blazing foliage is drawing to a close. Helen Hartness Flanders, a Springfield native, is not worrying herself with capturing the foliage, though. She is busy catching a quarry quite as ephemeral as the autumn leaves: folk songs.

Flanders is a songcatcher, devoting her life to, in her words, “prospecting for a common everyday variety of great literature alive today in New England.” On this November day, she and her recent acquaintance Alan Lomax are making the short trip to North Springfield in search of songs. Lomax, the famed songcatcher of southern Appalachia, had heard of Flanders’ work collecting ballads in northern New England; he has brought his expertise and newfangled recording technology to Vermont to try his hand at prospecting in these fertile hills.

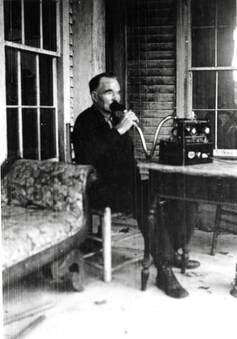

The recording device is a wonder to Flanders. A disc recorder, it cuts songs into a 12-inch disc with far greater quality and durability than Flanders’ wax cylinder Dictaphone. Many of her cylinders are already deteriorating rapidly, after less than a decade of collecting. She resolves to upgrade her own recording equipment; the Speak-O-Phone disc recorder will serve her faithfully for another decade until she upgrades again in 1949 to magnetic tapes.

In North Springfield, Flanders and Lomax stop at the home of Mrs. John Fairbanks. “I knew there were certain farmhouses,” writes Flanders, “where the past lingers into the present in haunting, indescribable fashion.” Flanders had visited Mrs. Fairbanks a month previously and knew that hers was one such house. What better place for Lomax to begin his journey into the ancient world of New England balladry? After greetings and introductions, Lomax and Flanders settle down with Mrs. Fairbanks, the bulky disc recorder, incongruous with the old house, on a desk between them. With a few prompting words, Mrs. Fairbanks begins to recollect the songs and stories of her family’s past.

The year is 2021, and I sit in front of my laptop, earbuds in. I click the play button on the web browser, and immediately a crackling and popping transports me to another time.

After a few seconds, the crackling fades, and a woman’s voice with a gentle Irish brogue rises out of the hiss, midway through a sentence:

… The Pretty Maid Milking Her Cow is that it was cursed by a priest, who was called out one night to give the last rites to a dying person. On his way, he heard somebody singing the song, and was so entranced with the singing that he paused, until it was finished. He then went on to the person’s house who was sick, and as he got to the door, he met the Black Dog, and he knew then that he was too late. And so he cursed the singer, and the devil because he blamed the devil for holding him back, instead of going attending to the soul who had called for the last rite.

After a few hems and haws and advance excuses for an imperfect memory, Mrs. John Fairbanks continues, unfolding the bittersweet Irish melody of “The Pretty Maid Milking Her Cow” (see audio below): “It was on a bright summer’s morning that the birds sweetly tuned on each bough.…” Through the crackling of the record and the dust of decades, her voice rings clear, haunting and beautiful.

New England’s Songcatcher

Helen Hartness Flanders (1890-1972), the wife of U.S. Senator Ralph Edward Flanders, was a poet and avid supporter of music in her home state. She was a natural choice when, in 1930, the Committee on Traditions and Ideals of the Vermont Commission on Country Life selected her to lead a research project into the traditional music of Vermont. The goal was to find the old songs once common in Vermont and reconnect them with the people by publishing a book of lyrics and melodies.

She began with inquiries in local newspapers. “Do you know of any music—old songs or dances specially grown in Vermont?” she wrote in a letter to the Rutland Herald. “There must be Come-all-ye’s and Shanties and French-Canadian dialect songs, Nursery Songs and altered Welsh, English, and Scottish Ballads. Please try to remember where you have heard them and write me.”

Flanders did indeed find all of these song genres and more, but through the influence of Cambridge, Massachusetts, scholar Phillips Barry, she quickly narrowed her search to those specimens most interesting to musicologists of the day: ballads of the British Isles—especially those 305 ballads, called the “Child Ballads,” cataloged by 19th-century folklorist Francis James Child—and very old American songs in the British ballad style.

Scholarly opinion had it that musical traditions brought to the New World from Britain had completely disappeared by the 1930s, with one notable exception: southern Appalachia, a rural, mountainous region ranging from southwest Pennsylvania to northeast Mississippi. Songcatchers like Alan Lomax had discovered communities in those mountains where the songs of the Old World were alive and well, even when many of those songs had already died out in their native lands.

Phillips Barry had a hunch that, unbeknownst to the scholarly world, the British Ballad tradition was just as healthy in northern New England. With Flanders, he set out to prove it by collecting Child Ballads. The excitement of “prospecting” for Child Ballads fueled Flanders’ commitment to the project, and when the Vermont Commission’s funding ended in 1931, Flanders funded her collecting herself and expanded her scope to all of New England. “As to our tracks,” she wrote, “some led to islands off the coast of New England, some into New York state and as many were in the heart of cities as along backcountry roads in valleys or near the skyline.” Flanders’ discovery of the “Edward Ballad,” a Child Ballad sent to her by Mr. George J. Edwards of Burlington, Vermont, was a watershed moment for the two songcatchers. It was the 48th Child Ballad they found in Vermont, prompting Barry to write to Flanders in a 1933 letter, “LITTLE VERMONT TIES BIG VIRGINIA: score 48 to 48!!!”

Across the River and Across the Sea

The old British ballads represented a historical and cultural tie to the Old World, of which many British descendants in New England were (and are) very proud. But heritage aside, the songs are fascinating in their depiction of a lost way of life and worldview. Many of them bear heartbreaking melodies and lyrics; many record lovers’ entanglements of centuries past. Others are silly, macabre, or just plain absurd.

“The Farmer’s Curst Wife” is a Child Ballad with many versions represented in the Flanders Collection, including recordings from Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. After attempting to plow his field with his dog and his sow (“and he went walloping round, the devil knows how”), a farmer receives a visit from the devil himself. The farmer is relieved to hear that the devil has come not for his oldest son but his “scolding old wife.” But when the devil swings the wife across his back and takes her to hell (“clickety-clack”), she proceeds in colorful fashion to murder the little devils waiting to chain her up. “Then another little devil peeked over the wall: ‘Carry her back, Master Devil, she will kill us all!’” And so, much to the farmer’s chagrin, the devil hauls her onto his back, “and like a darn fool he went tugging her back.”

Among the old American ballads is “Fair Charlotte,” (see audio below) found in Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and Massachusetts (and known in the Midwest as well). The song is a caution to all would-be vain young women. When her sweetheart rides up in his sleigh to pick her up for the New Year’s Eve ball, Charlotte laughs at her mother’s reminder to dress warmly: “To ride in blankets muffled up / I never will be seen!” But upon reaching the ballroom, her young man makes to help her from the sleigh—and finds Charlotte a “frozen corpse.”

Another ballad of American origin is “Margery Grey,” (see audio below) found on both sides of the Connecticut River—a chilling story of a young woman in northern Vermont who gets lost one evening walking home with her infant from her neighbor’s house. The infant dies, but the mother reappears months later in a New Hampshire village, having never crossed the Connecticut—she had wandered north and around its Canadian headwaters before finding civilization again.

“Young Strongbow,” (see audio below) also collected in Vermont and New Hampshire, tells the story of “a sprightly Red Boy from the woods” who goes to study at Dartmouth College. “In liberal arts and sciences,” the ballad tells us, “with White Boy he kept pace, / And few there were that ridiculed the color of his face.” One classmate, though, does “wantonly intrude” on “poor Strongbow’s peace,” but Strongbow merely tells the bully that he might find himself in need of Strongbow’s aid one day. “When steady years had rolled around on the rapid wheels of time,” the rude boy, now a captain, goes to war against the British, who have “engaged the Red men on their side.” The captain is captured, “and to atone for warriors slain, they sentenced him to die.” The warriors tie him to a tree and dance around him with torches, until a chieftain breaks the ring and confronts the captain. It is, of course, Strongbow. “Captain,” he says, “you know those Indians well; they never can forget / A favor or an injury when friends or foes are met.” The captain begs his life, for his family’s sake, and Strongbow replies, “Although they never can forget, those Indians can forgive. / The White Man set at liberty; brave comrades, let him live.”

In 1941, Flanders donated her collection, as well as the majority of the funds to maintain and grow it, to Middlebury College in Middlebury, Vermont. Musicologist Marguerite Olney (1897-1976) was hired as the collection’s curator, ushering in a new era for the collection. As Flanders’ health declined (and she assumed the duties of senator’s wife in 1946), Olney increasingly took over the task of traveling to correspondents to collect songs. Under her influence, the collection’s scope expanded once more, to “be made thoroughly representative of the folk tradition of the region,” Olney wrote.

Songs collected during Olney’s tenure include French-Canadian songs like the curious “Un Petit Sauvage” (“A Little Wild One”—Merritt Earl, the singer, describes the refrain as being “in Indian”), African American spirituals like the bold hymn “I Do, Don’t You?” (see video below) and logging camp songs like “The Alphabet Song” (“K is the keen edges on our axes we keep, / and L is the lice on our backs they do creep”; see video below).

Flanders and Olney collaborated on several publications, including “Ballads Migrant in New England,” a book of selected songs and anecdotes from the songcatchers’ travels, published in 1953. “Making My Will,” one of the book’s gems collected in Rhode Island, recounts a man’s bequests to his “dear wife,” among them “A greasy hat, my old tom cat, / A yard and half of linen.” Another from Rhode Island, “Gentleman Froggie,” tells of the whimsical courtship and wedding of Gentleman Froggie and Mistress Mouse, at the end of which “they took a sail upon the lake / And were all gobbled up by a big black snake.”

The End of an Era

The Vermont Commission’s original 1930 project was spurred on in part by an anxiety that a way of life was dying out, and a literature along with it. With the advent of radio, and later television, popular music was increasingly supplanting oral ballad traditions in New England homes. To preserve those traditions, collecting the songs before their last generation of keepers died out was imperative. Over the last decade of their collecting, Flanders and Olney revisited many singers they had collected from early on. Those singers became fewer and fewer, though; the songcatchers were watching the disappearance of a generation, the very event that their collecting had anticipated.

In the late 1950s, perhaps influenced by a falling-out between the two collectors, Flanders withdrew her funding from the Flanders Ballad Collection. The financial blow effectively ended the collecting enterprise, with Middlebury College eliminating Olney’s position of curator in 1960. The collection of roughly 4,800 cylinders, discs, and tapes fell into obscurity, suffering damage from neglect, but in 1978 most of the collection was transferred to cassettes for the Library of Congress Archive of Folk Song. Middlebury College has since rehoused the collection in a state-of-the-art archival facility, and today, thanks to a Middlebury College Special Collections digitization project from 2013 to 2015, the recordings are available for anyone to peruse on the Internet Archive.

I studied music as an undergraduate at Middlebury College, with a focus on vocal performance, but it wasn’t until, as a senior in 2015, I attended a College talk on fiddle tunes from the collection that I first encountered Flanders’ work. It seems the digitization project has lifted Flanders’ recordings out of obscurity; Preservation Manager and Special Collections Associate Joseph Watson informs me that several undergraduate classes, as well as independent researchers like myself, make regular use of the collection now. I have certainly fallen for the romance of Flanders’ scratchy recordings, the surprise, humor, anguish, and joy of the lyrics, the tone-deaf singers and the strikingly crystalline voices, and the accents and attitudes of a bygone era.

Robert Frost, in his introduction to “Ballads Migrant in New England,” writes of the rough-hewn nature of the folk ballad: “It may seem to be going to pieces, breaking up, but it is only the voice breaks with emotion.” Helen Hartness Flanders, Marguerite Olney, and the singers and scholars who aided their work have saved a vast treasure trove of literature from breaking up entirely. It is our turn, now, to discover riches untold.

Jack DesBois is a singer, actor, writer, and storyteller from Massachusetts. He created “V is the Valley: a Concert-Conversation with the Folk Songs of New England,” which he offers to schools and cultural organizations. His website is JackDesBois.com.

The digitized audio files of the Helen Hartness Flanders Ballad Collection can be accessed online at archive.org/details/helenhartnessflanders. The “Index to the Field Recordings in the Flanders Ballad Collection" is a useful guide for navigating the collection and provides interesting background information in its introduction.

Selected Songs from the Flanders Ballad Collection

Audio and video files of several of the songs mentioned in the article, including audio taken directly from the Collection and new recordings by the author.

“The Pretty Maid Milking Her Cow" - a compilation of two fragments from the Flanders Ballad Collection, the first sung by Meg Shurtleff of Montpelier, Vermont, the second by Lena Bourne Fish of East Jaffrey, New Hampshire. Note the two different melodies.

“Fair Charlotte" - a fragment from the Flanders Ballad Collection sung by Mrs. Charles Scott of Westboro, Massachusetts, followed by a studio recording of the remainder of the ballad sung by Jack DesBois.

“Margery Grey" - studio recording sung by Jack DesBois.

“Young Strongbow" - studio recording sung by Jack DesBois.

“I Do, Don't You?" - video recording in Topsfield, Massachusetts, sung by Jack DesBois.

“The Alphabet Song" - video recording in Topsfield, Massachusetts, sung by Jack DesBois.